I’m sure we can all acknowledge the pressing fact that the surroundings we grow in shape us into who we are today. Mary Shelley certainly felt just the same as evidenced by her short book, Mathilda, published posthumously in 1959.

The story of Mathilda begins with the title character just about to commit suicide. Completely done with her own existence, she hopes to explain to her friend, Woodville, just how she came to be in her situation. It transpires that Mathilda’s father had confessed his romantic love for her in a letter, thus prompting Mathilda to sift through the debris of her life.

As we know from her previous novel, Frankenstein, Shelley was particularly obsessed with the notion of creation, in metaphysical ways as well as ordinary. The very first sentence truly sets the tone for the rest of the story.

“It is only four o’clock; but it is winter and the sun has already set: there are no clouds in the clear, frosty sky to reflect its slant beams, but the air itself is tinged with a slight roseate colour which is again reflected on the snow that covers the ground.”

While this is a particularly long opening line, it is vital in birthing the atmosphere Mary Shelley forged. Mathilda isn’t just about creation, however, for further quotes indicate themes of feeling trapped in one’s own being:

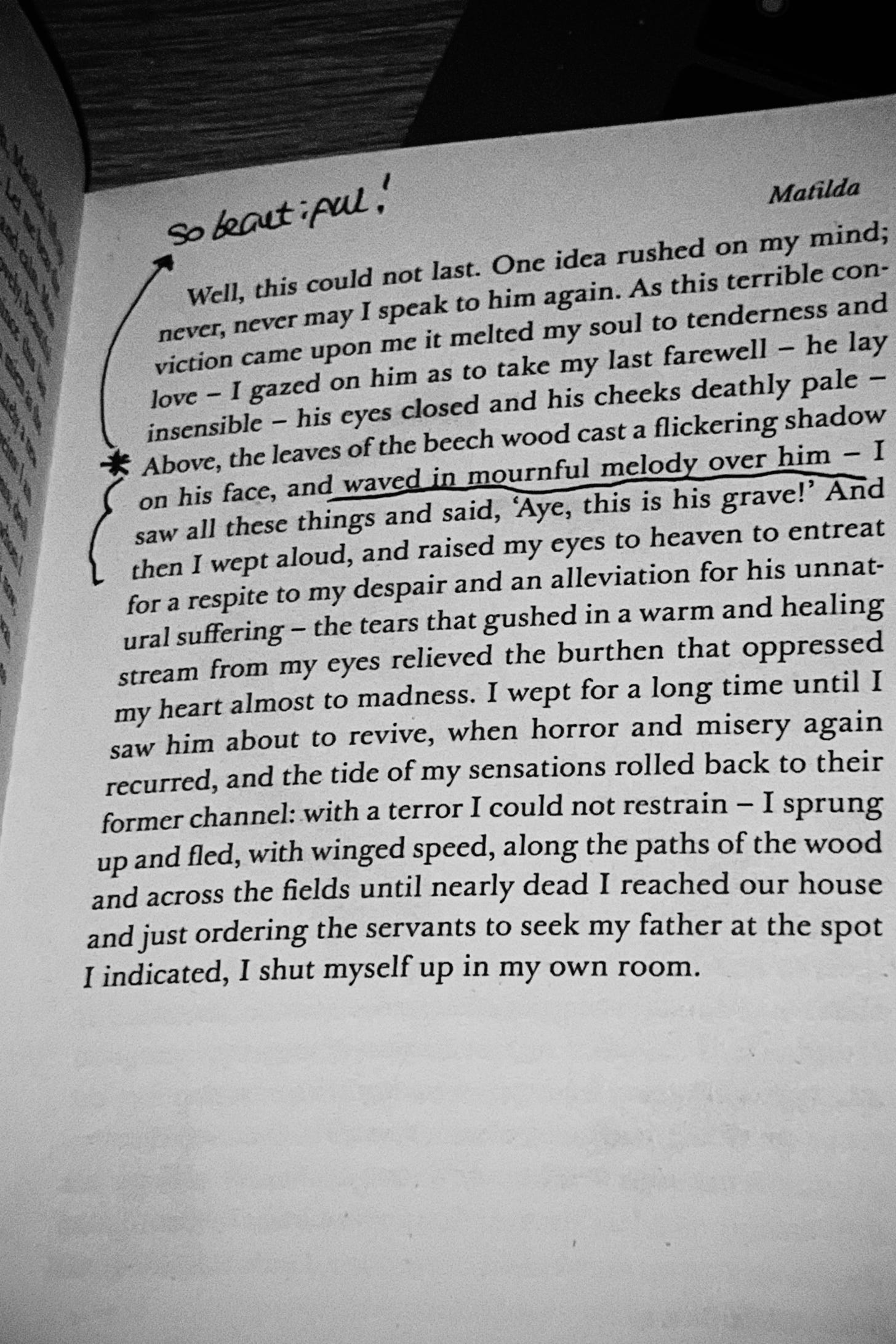

“…I shut myself up in my own room.”

While reading Mathilda, I noticed similarities between this book and Nabokov’s Lolita. The lines between father and lover are explored in both works, often mythologised. If we look at the Greek myth of Myrrha, there are stark links between all the works of Shelley and Nabokov. The connection to Lolita is especially pertinent for in the myth, Myrrha tricks her father into sleeping with her. When he discovers her identity, he draws his sword. Myrrha flees across Arabia. After nine months, she asks gods for their help. They take pity on her and transform her into a myrrh tree, the form in which she gives birth to Adonis.

If we apply this myth to Mathilda, the birth of Adonis could be seen as the physical representation of change. Mathilda is irrevocably changed by her father’s confessions, and is inevitably a different person entirely. This quick decline in mental state can be represented by the birth of a new life caused by prior events.

One could argue that Mary Shelley may have been the first to express ideas of the domino effect. This is backed up by Mathilda’s narration of her upbringing:

“How often have I wept over that letter which until I was sixteen was the only relic I had to remind me of my parents.”

The watchmaker theory is a teleological argument for the existence of God: the belief that the design must have a creator. As beings, who are our creators? Our parents make us and bring us to life, but what happens if you play a part in the untimely death of your mother? Well, that is precisely what happened to poor Mary Shelley. When she was just eleven days old, her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft died of sepsis—induced by retained placenta. Knowing she was the probable cause of her mother’s death, the acts of life and death cemented themselves in Shelley’s mind for her future work.

There are claims that Mathilda is biographical, but this is often disputed. We may never know if Mary Shelley’s father, William Godwin, had sordid feelings for this daughter. In fact, he was so disgusted by the book that he failed to return it to Shelley after she had sent it to him to be published. After Percy-Bysshe Shelley’s death by drowning, Mary thought the story quite ominous, saying of herself in an 1882 letter to Maria Gisborne:

“…driving (like Mathilda) towards the sea to learn if we were to be for ever doomed to misery.”

Compiled and edited by Elizabeth Nitchie, Mathilda was published posthumously in 1959. This is known as her other popular novel, after Frankenstein. Mary Shelley had always been haunted by her mother’s death, and even in her own, she cannot rest for her son, Percy Florence, and his wife went against Shelley’s wishes. Mary wanted to be buried with her parents, but as Percy and Jane did not like the graveyard of St. Pancras, they placed her at St. Peter’s Church in Bournemouth.

Ultimately, Mathilda is but a philosophical exploration of creation, much like Frankenstein. Though one could argue that the former is much closer to reality. Whatever the case, Mary Shelley was a woman with a lot of baggage: baggage she carried in her blood for the rest of her life.